Connected to the many watercraft cared for at The Canadian Canoe Museum are stories that speak to relationships between people, the land and the natural environment. These stories captivate audiences, inspire conversations and encourage diverse understandings of our shared cultures and histories. Join us in celebrating Indigenous History Month by diving into some of our favourite books and stories by Indigenous authors!

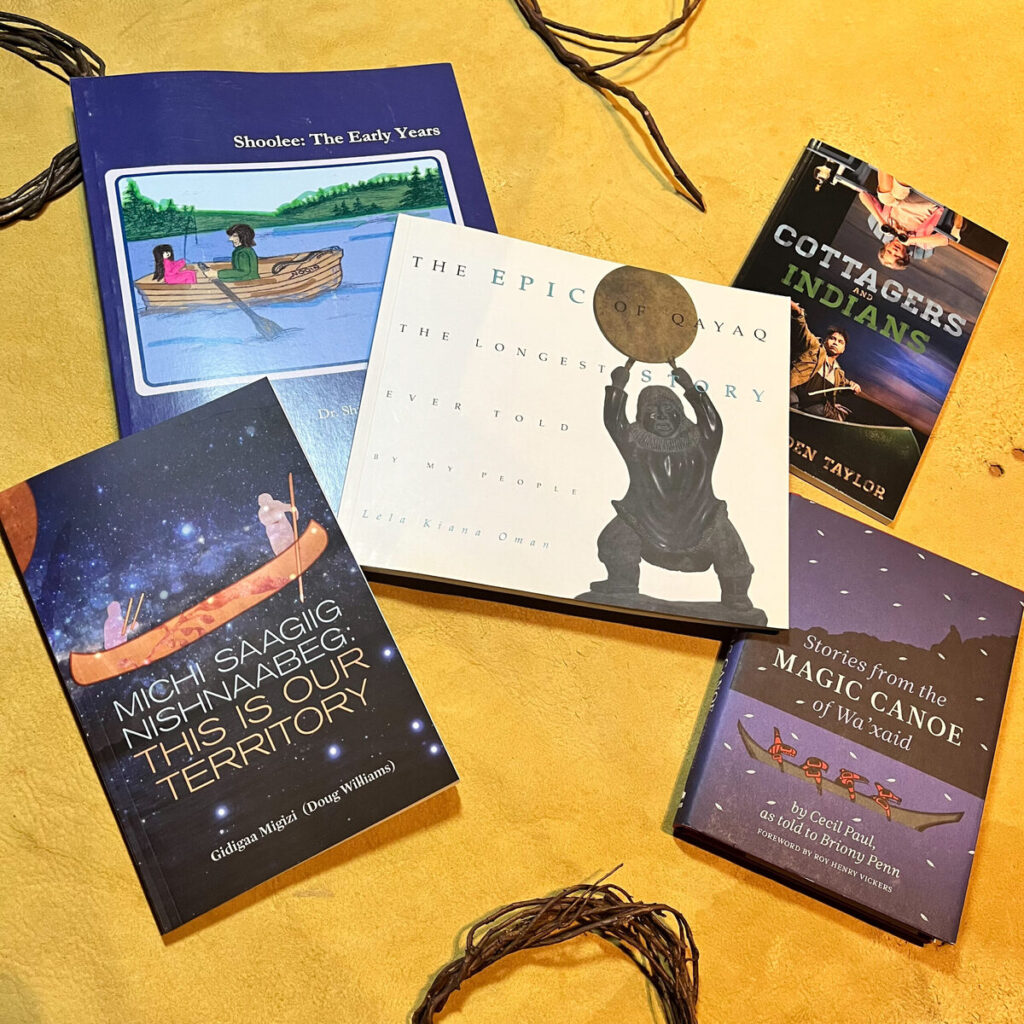

1. “Shoolee: The Early Years”

by Dr. Shirley Ida Williams-Pheasant

“Shoolee – The Early Years” is about a young girl growing up within the Anishinaabe way of life of hunting, fishing, trapping, gathering and knowing the importance of listening and being aware of the land. It is also a response to inspire Anishinaabeg to write about their history, language and culture and to share this. The book is about Shirley or Shoolee as she was also known, her brothers and sisters, father the fisherman and hunter and trapper, and her mother. There are also traditional teachings, making crafts and stories about school, farming. This book is in Anishinaabemowin and English.

2. “Cottagers and Indians”

by Drew Hayden Taylor

“Cottagers and Indians” is about manoomin, an Anishnawbe ‘good seed’ planted around a lake and which stands above the waterline, but it is also about Gertie, Justin and Marie. The seed causes consternation with cottagers who argue that it is hampering swimming, fishing, boating and property values.

This play is a conversation between Arthur Copper, grain planter and Indigenous man and Maureen Poole, well-to-do non-Indigenous woman in her mid-fifties, and the audience through the lens of Indigenous and non-Indigenous land and food sovereignty issues set in the context of a lakeside spat between the two protagonists. Leanne Betasamosake Simpson provides the afterword on land and reconciliation: having the right conversations, reproduced with permission.

Shortlisted 2020 for The Stephen Leacock Memorial Medal for Humour.

3. “The Epic of Qayaq: The Longest Story Ever Told by My People”

by Lela Kiana Oman

This is a splendid presentation of an ancient northern story cycle, brought to life by Lela Kiana Oman, who has been retelling and writing the legends of the Inupiat of the Kobuk Valley, Alaska, nearly all her adult life. In the mid-1940s, she heard these tales from storytellers passing through the mining town of Candle, and translated them from Inupiaq into English. Now, after fifty years, they illuminate one of the world’s most vibrant mythologies. The hero is Qayaq, and the cycle traces his wanderings by kayak and on foot along four rivers – the Selawik, the Kobuk, the Noatak and the Yukon – up along the Arctic Ocean to Barrow, over to Herschel Island in Canada, and south to a Tlingit Indian village. Along the way he battles with jealous fathers-in-law and other powerful adversaries; discovers cultural implements (the copper-headed spear and the birchbark canoe); transforms himself into animals, birds and fish, and meets animals who appear to be human.

4. “Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg (This is Our Territory)”

by Doug Williams

In this deeply engaging oral history, Doug Williams, Anishinaabe elder, teacher and mentor to Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, recounts the history of the Michi Saagiig Nisnaabeg, tracing through personal and historical events, and presenting what manifests as a crucial historical document that confronts entrenched institutional narratives of the history of the region.

Edited collaboratively with Simpson, the book uniquely retells pivotal historical events that have been conventionally unchallenged in dominant historical narratives, while presenting a fascinating personal perspective in the singular voice of Williams, whose rare body of knowledge spans back to the 1700s. With this wealth of knowledge, wit and storytelling prowess, Williams recounts key moments of his personal history, connecting them to the larger history of the Anishinaabeg and other Indigenous communities.

5. “Stories from the Magic Canoe of Wa’xaid”

by Cecil Paul, as told to Briony Penn

A remarkable and profound collection of reflections by one of North America’s most important Indigenous leaders.

My name is Wa’xaid, given to me by my people. ‘Wa’ is ‘the river’, ‘Xaid’ is ‘good’ – good river. Sometimes the river is not good. I am a Xenaksiala, I am from the Killer Whale Clan. I would like to walk with you in Xenaksiala lands. Where I will take you is the place of my birth. They call it the Kitlope. It is called Xesdu’wäxw (Huschduwaschdu) for ‘blue, milky, glacial water’. Our destination is what I would like to talk about, and a boat – I call it my magic canoe. It is a magical canoe because there is room for everyone who wants to come into it to paddle together. The currents against it are very strong but I believe we can reach that destination and this is the reason for our survival. —Cecil Paul

Who better to tell the narrative of our times about the restoration of land and culture than Wa’xaid (the good river), or Cecil Paul, a Xenaksiala elder who pursued both in his ancestral home, the Kitlope — now the largest protected unlogged temperate rainforest left on the planet. Paul’s cultural teachings are more relevant today than ever in the face of environmental threats, climate change and social unrest, while his personal stories of loss from residential schools, industrialization and theft of cultural property (the world-renowned Gps’golox pole) put a human face to the survivors of this particular brand of genocide.

Told in Cecil Paul’s singular, vernacular voice, “Stories from the Magic Canoe” spans a lifetime of experience, suffering and survival. This beautifully produced volume is in Cecil’s own words, as told to Briony Penn and other friends, and has been meticulously transcribed. Along with Penn’s forthcoming biography of Cecil Paul, Following the Good River(Fall 2019), “Stories from the Magic Canoe” provides a valuable documented history of a generation that continues to deal with the impacts of brutal colonization and environmental change at the hands of politicians, industrialists and those who willingly ignore the power of ancestral lands and traditional knowledge.

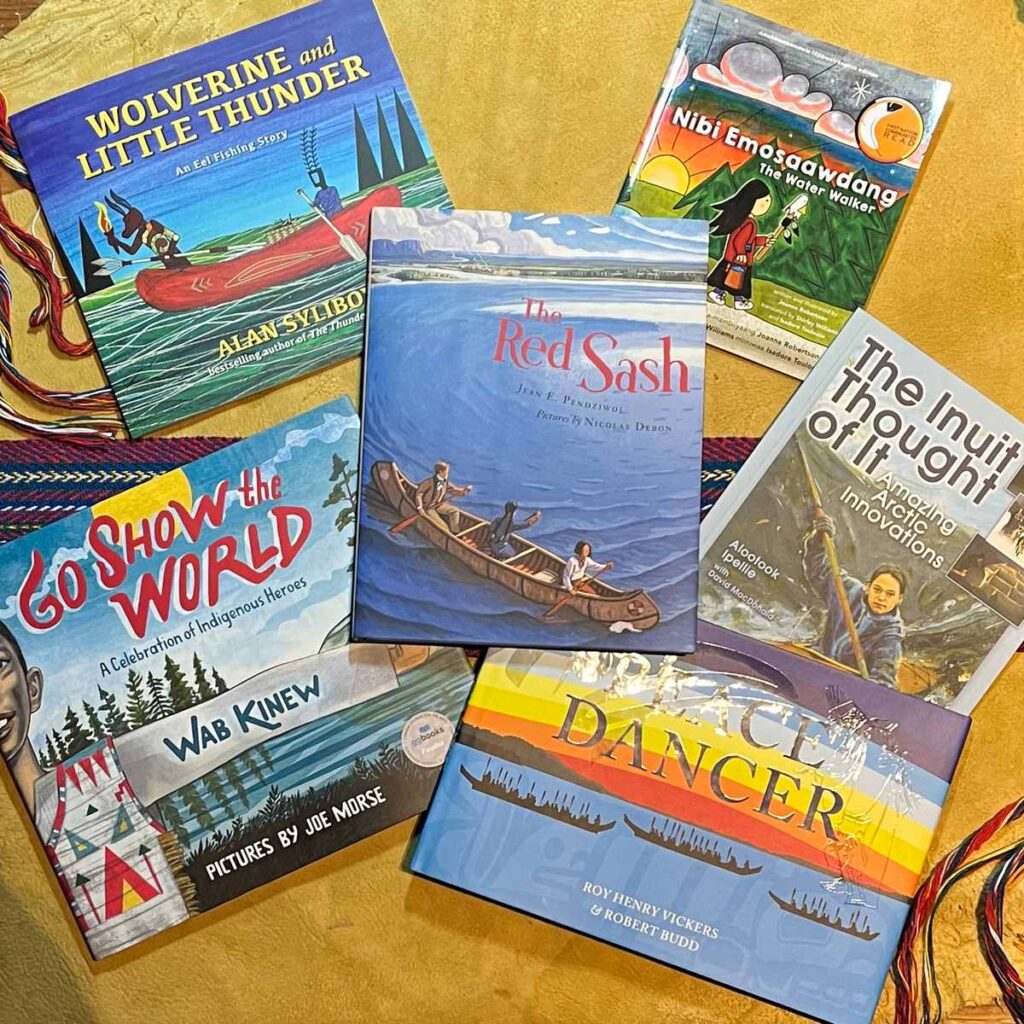

6. “Wolverine and Little Thunder – An Eel Fishing Story”

by Alan Syliboy

Celebrated Mi’kmaw artist behind The Thundermaker returns with a new story about friendship and the importance of traditional knowledge — now in paperback!

Longlisted, First Nations Communities Read, 2020, Children’s Award Jury-selected for the 2018-2020 From Sea to Sea to Sea: Celebrating Indigenous Picture Book collection (IBBY Canada)

From the bestselling creator of The Thundermaker comes another adventure featuring Little Thunder and Wolverine — a trickster, who is strong and fierce and loyal. The two are best of friends, even though Wolverine can sometimes get them into trouble. Their favourite pastime is eel fishing, whether it’s cutting through winter ice with a stone axe or catching eels in traditional stone weirs in the summer. But that all changes one night, when they encounter the giant river eel — the eel that is too big to catch. The eel that hunts people!

At once a universal story of friendship and problem-solving, Wolverine and Little Thunder is a contemporary invocation of traditional Mi’kmaw knowledge, reinforcing the importance of the relationship between the Mi’kmaq and eel, a dependable year-round food source traditionally offered to Glooscap, the Creator, for a successful hunt.

7. “Nibi Emosaawdang / The Water Walker”

Written and Illustrated by Joanne Robertson, Translated by Shirley Williams and Isadore Toulouse

Nokomis – our grandmothers – walk to protect our water, and to protect all of us.

The dual language edition, in Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe) and English, of the award-winning story of a determined Ojibwe Nokomis (Grandmother) Josephine-ba Mandamin and her great love for Nibi (water). Nokomis walked to raise awareness of our need to protect Nibi for future generations, and for all life on the planet. She, along with other women, men, and youth, have walked around all the Great Lakes from the four salt waters, or oceans, to Lake Superior. The walks are full of challenges, and by her example Josephine-ba invites us all to take up our responsibility to protect our water, the giver of life, and to protect our planet for all generations.

“Josephine Mandamin has inspired countless adults to care passionately about protecting the waters of the earth. Now through Joanne Robertson’s magical book, Josephine will inspire children to know they can change the world.” – Maude Barlow, The Council of Canadians and Water Activist

8. “The Red Sash”

by Jean E. Pendziwol, Pictures by Nicolas Debon

“The Red Sash” is the story of a young Metis boy who lives near the fur trading post of Fort William, on Lake Superior, nearly 200 years ago. His father spends the long winter months as a guide, leading voyageurs into the northwest to trade with native people for furs. Now it is Rendezvous, when the voyageurs paddle back to Fort William with their packs of furs, and North West Company canoes come from Montreal bringing supplies for the next season. It is a time of feasting and dancing and of voyageurs trading stories around the campfire.

With preparations underway for a feast in the Great Hall, the boy canoes to a nearby island to hunt hare. But once there, a storm begins to brew. As the waves churn to foam, a canoe carrying a gentleman from the North West Company appears, heading toward the island for shelter. The boy helps land the canoe, which has been torn by rocks and waves. Then he saves the day as he paddles the gentleman across to Fort William in his own canoe, earning the gift of a voyageur’s red sash.

9. “The Inuit Thought of It: Amazing Arctic Innovations”

by Alootook Ipellie with David MacDonald

Join authors Alootook Ipellie and David MacDonald as they explore the amazing innovations of traditional Inuit and how their ideas continue to echo around the world.

Some inventions are still familiar to us: the one-person watercraft known as a kayak still retains its Inuit name. Other innovations have been replaced by modern technology: slitted snow goggles protected Inuit eyes long before sunglasses arrived on the scene. Andother ideas were surprisingly inspired: using human-shaped stone stacks (Inunnguat) to trick and trap caribou.

Many more Inuit innovations are explored here, including:

- Dog sleds

- Shelter

- Clothing

- Kids’ stuff

- Food preservation

- Medicine.

In all, more than 40 Inuit items and ideas are showcased through dramatic photos and captivating language. From how these objects were made, to their impact on contemporary culture, The Inuit Thought of It is a remarkable catalogue of Inuit invention.

10. “Go Show the World”

by Wab Kinew, Pictures by Joe Morse

“We are a people who matter.” Inspired by President Barack Obama’s Of Thee I Sing, Go Show the World is a tribute to historic and modern-day Indigenous heroes, featuring important figures such as Tecumseh, Sacagawea and former NASA astronaut John Herrington.

Celebrating the stories of Indigenous people throughout time, Wab Kinew has created a powerful rap song, the lyrics of which are the basis for the text in this beautiful picture book, illustrated by the acclaimed Joe Morse. Including figures such as Crazy Horse, Net-no-kwa, former NASA astronaut John Herrington and Canadian NHL goalie Carey Price, “Go Show the World” showcases a diverse group of Indigenous people in the US and Canada, both the more well known and the not- so-widely recognized. Individually, their stories, though briefly touched on, are inspiring; collectively, they empower the reader with this message: “We are people who matter, yes, it’s true; now let’s show the world what people who matter can do”.

11. “Peace Dancer”

by Robert Budd and Roy Henry Vickers

“Peace Dancer” by fourth and final instalment of the award-winning and bestselling Northwest Coast Legends series by the award-winning artist Roy Henry Vickers.

In this 40-page picture book the children of the Tsimshian village of Kitkatla love to play at being hunters, eager for their turn to join the grown-ups. But when they capture and mistreat a crow, the Chief of the Heavens, angered at their disrespect, brings down a powerful storm. The rain floods the Earth and villagers have no choice but to abandon their homes and flee to their canoes. As the seas rise, the villagers tie themselves to the top of Anchor Mountain, where they pray for days on end and promise to teach their children to value all life. The storm stops and the waters recede. From that point on, the villagers appoint a chief to perform the Peace Dance at every potlatch and, with it, pass on the story of the flood and the importance of respect.

Roy Henry Vickers was born in 1946 in Greenville, B.C. His mother Grace Freeman was a schoolteacher of Yorkshire ancestry; his father Arthur Vickers was a half-Tsimshian, half-Heiltsuk fisherman. His grandfather, Henry Vickers, was a Heiltsuk who left Bella Bella to marry a Tsimshian woman in Kitlatka, a small village on Dolphin Island near Prince Rupert. Raised in Kitkatla, as well as in Hazelton and Victoria, Roy Henry Vickers graduated from Oak Bay High School in 1965. He worked as a fireman in Victoria prior to attending the Kitanmax (or Gitanmaax) School of Northwest Indian Art at ’Ksan on the Skeena River. The final page of this remarkable book explains the author’s connections to the peace dance that remains an important part of the potlatch.