Many followers of this blog might be familiar with the elegant paintings of voyageurs traveling in bark canoes by British-born artist Frances Anne Hopkins. Of the few artists who have left us an eyewitness graphic account of life in the canoe brigades of the Canadian fur trade, Hopkins’ art has always stood out for its elegant composition and its precision with detail. A bonus element is the “where’s Waldo” feature that the artist, a young woman in her late-twenties accompanied by her husband, is often portrayed sitting amidst the burly paddling crew on top of kit and cargo amidships.

Married to Edward Hopkins, 20-year-old Frances accompanied her husband to Canada, settling first in Lachine near Montreal. Edward initially served as secretary to Sir George Simpson, governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, and Frances accompanied her husband on many of his travels. The journeys that would serve as strongest muse for the young artist however would be several tours of inspection by voyageur canoe on the Upper Great Lakes and the Mattawa and Ottawa rivers between 1864 and 1869.

From her midships window-seat within what appears to be a 30-foot birch bark canot bâtard, Hopkins was witnessing and capturing the unique maritime lifestyle of the voyageur in an era when it had already begun to fade into history. However, she missed nothing in her portrayals. For instance, we can tell that the canoes in her various oils are “traveling light” on account of their higher freeboard. This would be consistent with an express canoe traveling on inspection. By contrast, there can be found accounts by anxious travelers describing their canoes, fully loaded with trade goods or furs, whose gunwales are sitting but six inches above the water!

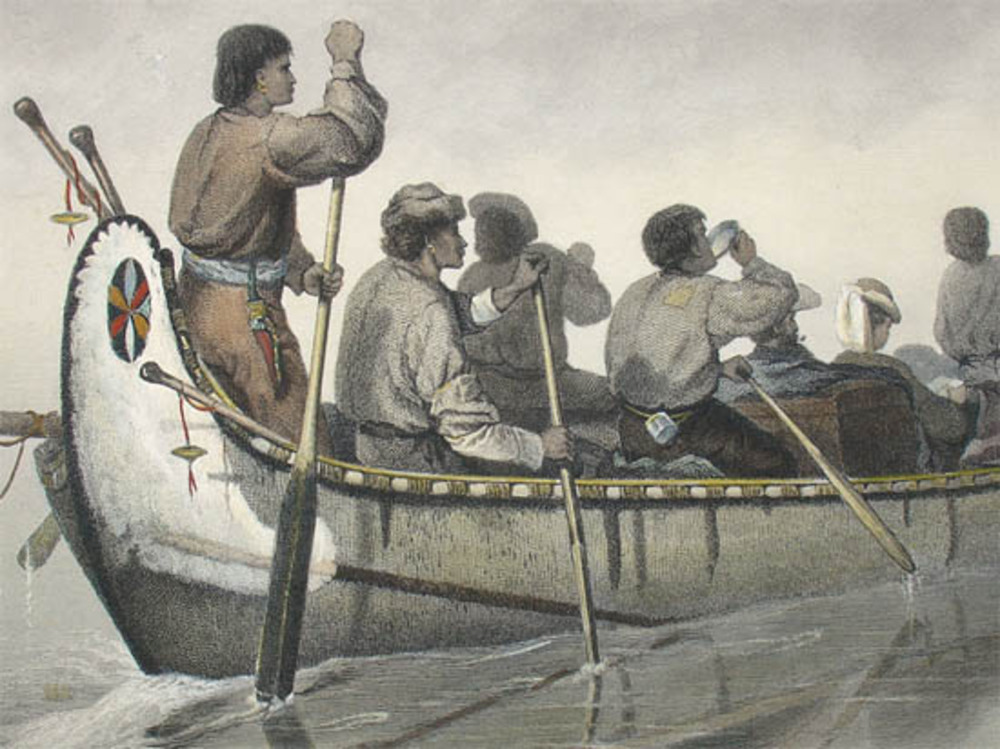

Looking at the stern end of the canoe in “Canoes in a Fog, Lake Superior”, we can see the grips of several extra paddles, likely a larger steering paddle for whitewater, right where we’d expect it behind the gouvernail or sternsman. Also portrayed, are the spars, lines and toggles that were part of the square sail rig. As part of the canoe’s agrès that also included lines, tarps, axe, a repair kit and so on, a sail was furnished with each canoe to take advantage of a following breeze on larger waters.

Many contemporary artists did not fully understand that the black, pitched seams on the outside of the canoe followed a fairly precise pattern that was dictated by the canoe’s very construction. Instead, the array of bark panels and waterproofed seams has occasionally suggested something like a quilt or perhaps the sealskin covering on a kayak. Hopkins’ contemporaries also often failed to notice that the spruce root lashings along the gunwales necessarily alternated with the position of each of the canoe’s ribs within. Hopkins’ renderings show that, whether she fully understood its unique construction or not, she missed nothing and portrayed the boats artfully but exactly as she saw them.

With this in mind, it is curious that she included (or rather, the boats she saw featured) a bead of spruce gum pitch along the canoe’s length right under the gunwales. True, there are tiny holes in the bark where the gunwale’s root lashings pierce through the bark skin. However, it would seem that if you were taking water through these perforations along the canoe’s upper rim, the boat was already swamping. This enigmatic detail is consistently portrayed in several of her major oils.

Ten years ago, we had the opportunity to build a fully operational 36-foot birch bark canoe. Of course, the research that went into this project drew heavily from Hopkins’ paintings and sketches, also contemporary journal entries, fur trade company records and also the excellent pioneering work of E.T Adney and Howard Chapelle. Although the original 36’ birch bark canoes have disappeared over the centuries, the Canadian Canoe Museum does have in its collection a silver miniature rendering of just such a canoe, presented as a gift to Sir George Simpson when Frances Hopkins would have been about 3 years old. The Canadian Canoe Museum has made good on its goal to match this boat against its historical folklore, putting this canoe through its paces by paddling, poling, lining, sailing and portaging the 350-pound hull under 8000lbs load and under various conditions. A few years ago, we joined Ray Mears and the BBC on the French River for a moving water adventure and to film a documentary. Consistent with the daily voyageur chores two centuries ago, we even created the necessity to provide some reconstructive surgery in the field!

These experiences lead me at last to a question that arises from a few of Hopkins’ paintings and that puzzles us still. A close look at the inverted hands of the devant (bow paddler) in “Shooting the Rapids” suggests that he is perhaps executing a cross-bow draw. Common in white water, this can be a handy, if clunky, response stroke in a tandem canoe or C1 but offers little effective sweep on a canoe that is nearly six feet wide, as long as a bus and carrying almost the same momentum. Perhaps Hopkins was using license to clear the paddle out of the devant’s face? Perhaps this was some mysterious “voyageur stroke” that really can offer but little power?” Is he planting a jam under the bow of the canoe to lever it across a channel? It really seems to fall apart for me when we also see the gouvernail in the stern of “Canoes in a Fog” using the same stroke from the back end of the canoe as they ghost along on a flat calm Lake Superior. Honestly, everyone knows that you just drag your paddle back there because no one can see you.